July 2, 2017

“The true seeing is when there is no seeing.” – Shen Hui (670-762), Chinese monk, founder of Japan Heze Zen Buddhist School

The first time a silver print by Paul Caponigro (born1932, American photographer) crossed my path in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the image held me in place as I grew ever so gently, ever so tenderly receptive to its sincerity and purity of being.

Rapport such as this is never talked about in public. Such dialogue is internalized and savored quietly within the cell of ones heart. Few people consider this love; rarely confess to experiencing it. Hardly anyone allows themselves the freedom to love this way: A love felt through the eyes.

Paul Caponigro, Two Pears, Still Life, gelatin silver print, 1964

Caponigro’s eye on the world reflects on the beauty, sensuality, and vibrancy within Nature. Each eyeful, a masterful meditation on how existence lives as and through every man, woman, child, including flora and fauna seen on Earth and beneath her oceans.

Paul Caponigro, Shell, tone silver print, 1960

One becomes aware of Spirit and its pranic force which touches us and hints at the possibilities of every Man’s capacity to reunite with Cosmos.

Paul Caponigro, Wreath for the Green Man, 1999

Caponigro’s work provides a glimpse, a glimmer of what it means to create from a state of awareness. His images and how they are developed contain the language of simplicity, and echo eternity. He may not have meant for them to carry a divine presence, but in their sheer nakedness, presence cannot be denied.

In the practice of Nalanda Miksang the flash of perception, that initial spark, the moment that catches our line of sight stuns the active mind. Awareness of and to, focuses on the detail, the aspect that would go unnoticed. Awareness jolts the mind awake, ever mindful of the present.

The resulting image and its appearance is in no way manipulated or doctored. The thing speaks for itself and carries its own life force.

Chogyam Trungpa, Texaco

Chogyam Trunga, Tractor

“When we draw down the power and depth of vastness into a single perception, then we are discovering and invoking magic. By magic we do not mean unnatural power over the phenomenal world, but rather the discovery of innate or primordial wisdom in the world as it is.” –Chögyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, ‘Discovering Magic’ from Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior.

Coming from a Hindu tradition, Avatar Adi Da Samraj, the images in his sacred photographic art, dimensions both human and cosmic, overlap and transcend. What is perceived does not necessarily have to be understood but felt, as this Spiritual Master relates below:

Adi Da Samraj, Pear Shape

Adi Da Samraj, Lotus

“Fundamentally, the images I make and do are simply to be felt. It is the perceptually-based feeling-response — and not merely an intellectual understanding — that is required. When you are viewing the images, take the time to simply, tacitly feel them — without trying to think of something to say about them. You do not have to “figure them out”. Simply participate in the images, by means of unguarded feeling-perception.” -from You Are The Surface Space of My Image-Art.

Awareness comes through different angles in the images perceived by photographer Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976).

In the early 1900’s, Cunningham focused on botanical and landscape photography. Her major work flower portraits that included her well known, aesthetically pleasing Magnolia series.

Imogen Cunningham, Magnolia Blossom, Silver Gelatin Print, 1925

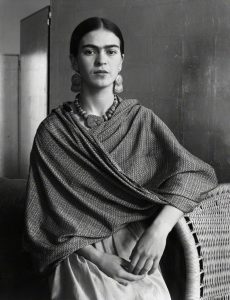

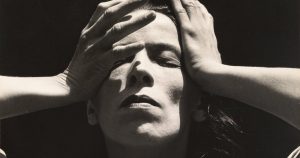

During the early 1930’s, Cunningham began experimenting with photographic papers, sepia tones, and photographing famous personages as artist Frida Kahlo, Martha Graham, musicians, painters, and actors. Cunningham explored the portrait and the human form for profit. Yet her work penetrates the superficial, exhibits an eye that peers into the soul of her subjects and places it on display for all of us to witness.

Imogen Cunningham, Frida Kahlo, Portrait, 1931

Imogen Cunningham, Martha Graham, Portrait, 1931

“One must be able to gain an understanding at short notice and close range of the beauties of character, intellect, and spirit so as to be able to draw out the best qualities and make them show in the outer aspect of the sitter. To do this one must not have a too pronounced notion of what constitutes beauty in the external and, above all, must not worship it. To worship beauty for its own sake is narrow, and one surely cannot derive from it that aesthetic pleasure which comes from finding beauty in the commonest things.” – Imogen Cunningham

Thomas Merton (Trappist monk, poet, photographer 1915-1968) utilized a contemplative approach to express his vision. Pictorially, what he wanted his photographs to reveal was the subject’s spiritual and intellectual transcendence.

Instead, what he discovered cast a different light on life and Spirit beyond what Christianity understood to be mysticism.

Thomas Merton, Zen Photography, Solitary Chair

Thomas Merton, Zen Photography, Bark

“…it seems to me that mysticism flourishes most purely right in the middle of the ordinary. And such mysticism, in order to flourish, must be quite prompt to renounce all apparent claim to be mystical at all.” Merton attributes his increasing sense of awareness to the practice of Zen.

Thomas Merton, India, 1968

During a walk through the fields of his monastery, Merton, observes a flock of deer, and describes the experience in his journal:

“I watched their beautiful running, their grazing… Every movement was completely lovely, but there is a kind of gaucheness about them sometimes that makes them even lovelier, like girls. The thing that struck me most–when you look at them directly and in movement–you see what the primitive cave painters saw. Something you never see in a photograph. It is most awe-inspiring. The ‘spirit’ is shown in the running of the deer. The deer-ness that sums up everything and is sacred and marvelous.”

“The deer reveals to me something essential, not only in itself, but also in myself: Something beyond the trivialities of my everyday being, my individual existence. Something profound. The face of that which is both in the deer and in myself.”

Merton calls his poetic sensibility his “contemplative intuition,” which he observes is “perfectly ordinary, everyday seeing–what everybody ought to see all the time.”

Unfortunately, Thomas Merton dies before visiting Japan, before he experiences the way of Zen. He fails to live from the standpoint of emptiness, relate from the place of no-mind, of no-self, where the false personage that he or she identified with no longer exists or is true.

Therefore Merton’s understanding of Zen is a simplistic understanding of Zen’s potential, whereby he writes: “But the chief characteristic of Zen is that it rejects all systematic elaborations in order to get back as far as possible to the pure, unarticulated and unexplained ground of direct experience. The direct experience of what? Life itself.”

Even so, Merton’s intellectual understanding of Zen doesn’t interfere. Still his images continue to transmit so much more.

There are artists who understand that this kind of insight, perceived via a work of art, is defined by the one who is doing the observing, what he or she adds, by what he or she perceives, and what awakens in him or her… Much can happen at any moment with awareness in the act of creation.

Consider these works by photographer Paul Strand, 1890-1976, USA:

Paul Strand, Shadow

Paul Strand, Hidalgo, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1933

Strand’s are darkroom images: photographs produced with the kind of precision and exactitude required of a master technician familiar with his tools and his capacity to picture what he sees.

Strand portrayed the world as it presented itself through the lens. Images presented themselves to him and he was fortunate to have been present to their calling.

Very few digital images capture the richness, the intensity or reach the magnitude and height of proficiency expressed in these labours of love. Each and every one of his images has a distinct voice, a unique and living, undying presence.

Surely this has to do with the artist’s, the creator’s, his and hers awareness of their unique expressions; the individual’s talent and point-of-view, and whether or not he or she is connected to that place where existence has its say in what matters.

Ultimately like most arts that we consider contemplative, whether it involves music, drawing, painting, writing, journaling, singing, dance, textile arts, and/or photography is not meditation.

Each and every one is a practice in awareness.

Each of the arts, including photography is an exercise that expands consciousness, helps to quiet the verbal mind, whereby we yield to, connect with, and have space for divine transmission to reveal itself.