April 3, 2017

The Bonfire, by Kunikida Doppo (1871-1908)

Many years ago, I read Kunikida Doppo’s short story, The Bonfire, and fell in love with his writing. Written like haiku, in length it is a slice of poetic verse; a story dense with unforgettable imagery.

I found this translation online, listed as a work in Public Domain. After reading this version, once again I was inspired by the images the story evoked.

Inspired to create, I composed a series of photo montages, and below each work I chose phrases from Doppo’s work, text that pose as haiku all on their own.

This wonderful translation by C.E. Zambrano, a student of Japanese, does the piece justice poetically. The graciousness and delicacy of Doppo’s words are not lost. To read Zambrano’s comments on poetic verse and use of tenses, including End Notes visit https://lostfoundintrans.wordpress.com

Thank you Kunikida Doppo for the legacy of your work, and thank you C.E. Zambrano for a translation that is true to the original.

Enjoy!

The Bonfire

Putting his back to the north wind, legs thrown out over the bluff amid white dunes and withered grasses, watching the dimming light of the sun sink down toward the Izu Mountains, and waiting for his father’s boat, already late, to return from the open sea—how lonely, how utterly miserable the young boy from Zushi must feel, deep in his heart.

towards the Izu Mountains waiting for his father’s boat – already late

The reeds that grow thick along the bank of the Gosaigo River rustle in the salt breeze. Beneath them the ice which formed at high tide—unseen in the dead of night, broken by the morning’s receding tide yet unthawed by the sunlight hours—draws a white line along the edge of the water in the dim twilight. Were a traveler to rest his weary legs here, would he be able to glance about absently and continue on his way, unaffected? Looking back one sees that place there which was once the Rokudaigozen Forest,2 and even now, seven hundred years later, it evokes deep emotion in the heart of man. A cold autumn wind sounds shrilly in the treetops.

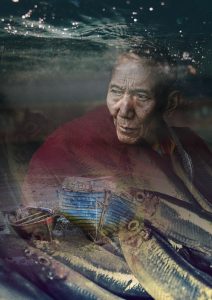

Along this muddy, gently flowing river one might imagine an old tune floating by with the fallen leaves from a boat rowing upstream, the harbinger of a frosty night. But no, no—you look and look, and all you see is a man—whether a farmer or a fisher, it’s hard to tell—who speaks not, nor laughs, nor sings, forlornly rowing along.

floating by fallen leaves – from a boat rowing upstream

The figure of a farmer shouldering his hoe, and the bridge upon which he walks, are reflected dimly on the surface of the river; soundlessly the boat passes through, scattering this image and disappearing into the reeds the next moment.

Two young men from town astride saddleless horses quietly make their way along the shallows at the mouth of the river as the last rays of sunlight waver upon this narrow strip of shore3—what a picturesque scene. Along the bank as far as the eye can see there is no sign of people. From the prow of a boat pulled up along the bank a crow cries and spreads its wings listlessly to make for the direction of Kamakura.

The end of December of a certain year. Though the year’s close approaches, a group of seven or eight boys between the ages of nine and thirteen years old—carefree, unburdened children of the wind—gather at the foot of the dunes and discuss various things, some standing, some sitting, some resting cheek in palm, elbows buried in the sand. The sun descends in the west.

bits of bamboo, a ladle with a broken handle brought by the storm

Their discussions apparently concluded, each boy begins to run about the water’s edge. Soon they have dispersed at random, from one edge of the beach to the other. The tide has receded far into the distance, and strewn on the beach are rotten planks of wood, a chipped bowl, bits of bamboo and wood, a ladle with a broken handle—all no doubt items brought by the storm two days ago. The boys gather these items and pile them up on the sand in a dry location well removed from the water. They are all thoroughly waterlogged.

What on earth are these boys doing on such a cold evening? The sun sinks ever lower in the west, and the clouds which fill the skies above Hakone and Ashigara4 are dyed a golden hue. The wind has died down—a boat returning to the Kotsubo inlet approaches the shore, lowers its sails and rows onward.

One boy, round-faced and dark-skinned but charming, picks up what looks to be the frame of a mirror, the glass of which has broken and fallen away. “It seems a shame to burn it.” “I guess, but it’ll definitely burn really well,” says the eldest boy while placing a log too big for his own strength. “That log probably won’t burn,” says the round-faced boy. “Well why should we leave anything unburned?!” the older boy says, angrily standing up. Another boy next to him shouts triumphantly, “Today’s the biggest haul yet!”

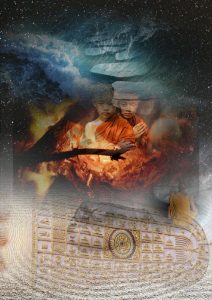

flames, crackling at the joints, frame of a mirror fallen away

The boys wish to burn their haul. They derive a wild joy from the crimson flames. They pride themselves for being able to run and jump over them. It is for this purpose they have gathered dried grass from the dunes. The elder boy stands up first and sets fire to the gathered grass as the others huddle round, waiting for the sound—now, or perhaps now—of bamboo cracking at the joints. But only the grass burns. Burns and vanishes. Smoke rises in thin wisps, but neither the wood nor the bamboo yields readily to the flames. The mirror frame is slightly scorched, and the log lets off some steam with a dubious sound. The boys take turns leaning low toward the sand and blowing into the flames, but the smoke brings tears to their eyes.

The sky over the sea is already darkening, and the island of Enoshima is difficult to make out. The cry of a thousand birds flying along the shore can be heard here and there, but, how lonesome, it seems too dark to see them. Yet there they are, those white points in the darkness. They are snipes, rising from the thick-growing reeds in a great flurry.

At this moment one of the boys had suddenly shouted5 “Look! Look! You can already see fire on the Izu Mountains. Why won’t our fire burn?” The other boys follow suit, standing and staring intently toward the sea. Indeed, across the bay flicker one or two points of light, like dubious will-o-the-wisps. No doubt these are fires lit by the people of the Izu Mountains to burn back the dried grasses. Oh, how the winter traveler at dusk, far from home, must cry for them, these fires he so yearns for in his heart.

“The Izu Mountains are burning! The Izu Mountains are burning!” the boys chant spiritedly, gazing across the bay, clapping their hands and dancing wildly. Ah how these innocent voices fill the lonely beach in the dim twilight, harmonizing with the whispering tide that runs up the southern edge of the inlet and draws its white line of ice there. High tide has come.

“It’s such a cold evening! How long will you play out on the beach?” a voice calls, but out past the dunes it goes unheard. The hearts of these boys race only for the flames upon the Izu mountains. “Aren’t you coming home?” “Aren’t you coming home?” two, three voices call, and one of the younger boys, finally hearing, suddenly runs off—“mother is calling. I’m giving up and going home.” Then the rest of the boys follow and race up the hill, yelling “yeah, yeah!”

Only the eldest boy, regretting the failed fire, looks back again and again as he runs up the hill, and, just as he is about to run down the other side, takes one last glance back to see a fire. “Look!? Our fire finally lit!” he yells. The others, astonished and skeptical, come back up the dune, gather at the summit and stand in a row staring down at the fire.

Indeed the gathered wood which refused to burn before is now caught in the wind, thick smoke rising in swirls, red tongues appearing and hiding again. The sound of cracking bamboo joints can now be heard and the children of fire dance where they stand. The fire has caught indeed, but the children do not return to it. They must go home, and so they merely rejoice with clapping hands and high delighted voices before racing together down the hill to the road along which their houses lie.

Both the sea and shore now lie in the darkness of a lonely winter night. The abandoned fire burns in solitude on the beach of Zushi.

black shadow, along the edge of the water a traveller

Suddenly a black shadow appears, approaching the fire along the edge of the water. An elderly traveler it is, having just crossed the Gosaigo River and heading toward Kotsubo road which runs along the beach. The sound of his footsteps rings heavily as he hastens at the sight of the fire.

“What a good fire,” the traveler exclaims feebly in a hoarse voice. Throwing his cane aside and hastily removing the pack strapped to his back, he thrusts his hands out over the fire. His hands shake, his knees tremble. “Truly, what a cold night,” he says through chattering teeth. The blaze bathes his face in its crimson light—the deep wrinkles and terribly sunken eyes, their light dim and unfocused.

His head and beard are both a dull white, and covered in dust—cheeks an earthy color, only the very tip of his nose is red.

Where might this pitiful traveler be from? Where might he be heading? Perhaps he is merely a homeless drifter with nowhere to go.

“A truly cold night!” he mutters to himself, shaking his whole body as though struck by some thought. He pleasantly rubs his face with his now-warm hands. His robes are terribly old, threadbare cotton showing in places; steam rises from their skirts which are closest to the fire. Dampened from the morning rain, even at this late hour they have yet to dry.

“Ah, what a pleasant fire!” he repeats as he picks up his cane and, using it for balance, thrusts a leg over the fire. Both gaiters and socks are a faded navy blue, and a pale pink-toe pokes out from them. The cracking bamboo sounds loudly, and though the great blaze threatens to scorch his leg, the old man does not withdraw it.

“Truly, a pleasant fire! Who in the world built it! I’m much obliged.” Falling silent, the man changes to the other leg. “These ten years since I left the happy hearth of my old home, I have never met with such a wonderful fire.” As he says this his eyes, staring into the depths of the flames, seem to be gazing at some far-off thing. Perhaps in the flames’ depths are drawn that hearth, just as it was in times long past. And, appearing vividly, his children, his grandchildren.

times past, gazing at some far-off thing, his children, his grandchildren

“The fire of old was wonderful, the fire now is sad—but no, no.6 The past is past. Now is now. This is a pleasant fire.” His voice is trembling. Roughly he throws his cane down again. He puts his back to the fire, faces the sea and bending back he pounds at his lower back with both fists. The vast sky he looks up at is clear, a deep black wrapped about the frost of the Milky Way, and spreading far down past the distant Izu Peninsula.

His body is now thoroughly warm, both skirts and sleeves completely dried. “Ah, who in the world built this fire? Who built it and for whom did they build it?” The old man’s heart is filled with deep gratitude and his eyes with glistening tears. There is neither wind nor wave, and the old man closes his eyes and listens to the sound of sand being steeped in the coming tide. In this moment he has completely forgotten even the sorrow of his lonesome wandering and returns now briefly to the old days of his childhood.

Ah, the fire is nearly out. Both the bamboo and wooden planks are burnt up. Only the great log still burns strong. The man did not think it would be so hard to leave the fire, even as it still burns. As he takes his leave, however, he feels suddenly reluctant to part with it. Making a ring with his arms he holds them at chest height above the fire as though embracing it. He blinks his eyes and thrusts his hips forward as though the time has come to leave, but as he makes his first two or three steps away from the fire, he scrapes together the unburnt bits of wood, adds them to the fire, and, watching the flames dance upward, smiles happily.

old man, footprints erased by the eternal waves

After the man leaves the fire gives off its crimson light, flickering uncertainly in the darkness of this desolate night. Night deepens, tide rises, and both the fire kindled by the boys and the roaming old man’s footprints are erased by the eternal waves.

*****